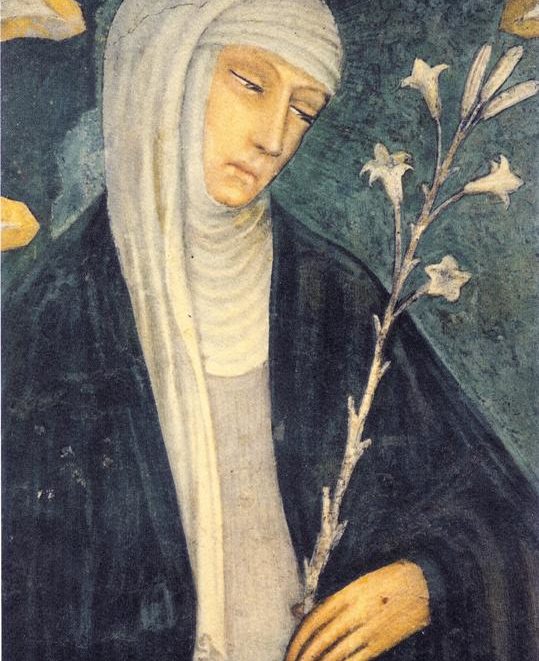

Wednesday 29th April is the feast of the great Dominican St. Catherine of Siena, founder of the Dominican Sisters. Her feast is especially timely this year as St. Catherine ministered and preached to victims of plague. Here is a meditation by Sr. Chiara Tessaris OP, of St. Catherine’s Dominican Convent in Cambridge, on St. Catherine’s work and what it might say for our lives.

The following meditation is based on Sigrid Undset, Catherine of Siena, (Sheed and Ward), London 1954 and Arrigo Levasti, My Sevant Catherine, (The Newman Press), Maryland 1954.

The Catholic Church teaches that “Fortitude is the moral virtue that ensures firmness in difficulties and constancy in the pursuit of the good. It strengthens the resolve to resist temptations and to overcome obstacles in the moral life. The virtue of fortitude enables one to conquer fear, even fear of death, and to face trials and persecutions. It disposes one even to renounce and sacrifice his life in defence of a just cause. (CCC 1808)

At times like the ones we are currently going through, it is perhaps worthwhile pondering the remarkable fact that the deep spiritual friendship that bounded together St Catherine of Siena and her spiritual director Fra Raymond of Capua was born out of the shared untiring self-sacrificing efforts they faced together during the Black Death plague that struck Siena in the summer of 1374. Far from possessing Catherine’s fortitude and spiritual as well as physical energies, Raymond nonetheless allowed the grace of God to challenge and transform his heart through the example of this remarkable courageous woman madly in love with her Lord and God.

When he first came to Siena, Raymond had felt a slight scepticism with regard to her. ‘I want you to know, beloved reader,” – he wrote- “that at the beginning, when I heard her praised and had begun to know her, I was rather incredulous. I tried in every way and by every means to find out whether her actions were inspired by God”. In 1374 the General of the Preaching Friars nominated Fra Raymond as Reader of Sacred Scripture at Siena, and Director of Dominican Studies, with the special charge of supervising Catherine and her fellow Tertiaries, and directing their activity for the greater glory of the Order and Christendom. We have no document to tell us of the first meeting between Catherine and Fra Raymond, but we know, that the new Dominican Reader was in Siena on August 1st, 1374, that is, during the worst of the plague and famine, when Catherine was sparing no effort to aid the sick and suffering including her family members.

Catherine’s brother Bartolomeo had returned from Florence only to die of the plague. Poor Lapa, Catherine’s mother, also lost to plague a daughter called Lisa, and eight of her grandchildren died of the Black Death. As Catherine dressed the small bodies she sighed: “These children at any rate I shall never lose.” She had good reason to fear that all was not well with her brothers. Stefano died in Rome about this time, and Benincasa, who was in Florence, seems to have grown bitter through adversity.

The plague devastated Siena—about a third of the inhabitants died of it. As so often during periods of common disaster the priests and monks showed their noblest side—even many of those who had been worldly and indifferent as long as they had been able to live a peaceful and comfortable life began to think of the responsibility laid on them by their calling, and risked their lives in surroundings filled with horror and despair to attend the sick, give the dying sacraments, and bury the dead. Carts rattled through the streets of Siena day and night full of blue-black corpses. People said that this time the plague was even more terrible than the time before. It struck people like lightning—a man might get up in the morning, apparently quite well, and be dead before evening. It was more infectious this time, too; the very air seemed to be full of it.

Tirelessly Catherine went from hospital to hospital, out of homes where the sick lay, to nurse them, pray to console them, wash and clothe the corpses for burial. Day and night, she moved among the victims of the plague, armed with a small lamp and a smelling-bottle which was supposed to be a protection against infection from the pestilential air.

On his arrival Fra Raymond found her absorbed in her care for others. His description of this epidemic in Siena shows signs of his own uncertainty, hesitation and fear. He had never before come into direct contact with so virulent a plague; his life until then, as a teacher and preacher, had been tranquil, and under his own control. Now all at once, he found himself surrounded by pain, despair and death, and naturally it was not easy for him to take a decisive step. Every day he saw this young woman, whom it was his duty to supervise and direct, careless of her own danger, living in the midst of the stricken multitude. He saw her entirely dedicated to her self-imposed task of healing their bodies, when possible, and zealously working for the salvation of their souls. Moreover, those of his own fellow friars who were most faithful to Catherine, Fra Tommaso della Fonte and Fra Bartolomeo Dominici, were accompanying and helping her. What could he do? What ought he to do? Although but lately arrived in the city, his own mission was delicate and of great importance; could he stay apart in a friary, like other Dominicans? Would it be right to put himself and his own safety first? Catherine’s example and words exhorted him to busy himself in the service of others. She was wont to say that he who had Christian charity—and she wrote this the following year to Fra Bartolomeo Dominici—lacked for nothing because he had ‘a fiery robe to protect him from the cold, food lest he perish of hunger, and a bed for his fatigue’. Moreover, Fra Raymond belonged to an active Order, and his inertia at such a moment might bring shame upon it. But to visit the sick meant he might die at any moment, and this threat, which he had never had to think about before and now overhung him at every turn, left him by no means indifferent.

Finally, his sense of duty and, above all, Catherine’s own example, roused him and he decided to visit the sick wherever and however they were. ‘I was obliged to risk my life to minister to the souls of my fellows’, he tells us, and this ‘obliged’ is very revealing. When he wrote this he was an old man, but as he recalls this chapter of his life, he seems to have before his mind those hours of fear that he had had to live through, and to feel again, very vividly, the effort t he had made to conquer his own timid and hesitating nature.

The apostolate shared with Catherine increased his admiration for her, and he became her devoted disciple when he saw her, in the name of God, heal some of his own friends.

Once resolved, he went about day and night seeking out and comforting the sick, as was his duty confident that “Christ is more powerful than Galen [the famous doctor] and divine grace is stronger than nature.” He continued to serve the sick fearlessly, for “the soul of one’s neighbour is more precious than a man’s own life.” As the panic began to spread many of the priests and monks also lost their courage and escaped to the country. Fra Raimondo and his faithful friends had to work even harder than before and they were not spared the test of faith in God and Catherine.

Raymond himself, feeling one night the symptoms of the plague in his own body, ran at once to Catherine to ask her to heal him, which she did at once. After praying for him, she told him to lie and rest while she went out and prepared some food for him. She returned and waited on him during the meal, and before leaving said seriously, “Go now and work for the salvation of souls, and thank the Almighty who has saved you from this danger.” And Raymond went back to his work as usual, while he praised God who “had given such power to a virgin, a daughter of man.”

Catherine herself paid the price for her tireless efforts and dedication to the sick and suffering. At the end of the summer she fell ill, presumably largely through overwork. She faced her illness with great joy and faith as she felt that she was approaching the fulfilment of her dearest wish, “to die and become one with her beloved Jesus Christ.”

Catherine not only loved the Lord more than her own life, but she also knew that there is no use in being anxious about it because we don’t have the power to add a single cubit to our life and even the hair on our head is counted (Mt 6.27, Lk 12.7). Her time had not come yet: on the day of the Blessed Virgin’s Assumption, Our Lady appeared again to Catherine and said that her Son wished her to live a little longer—He still had work which she was to do for Him on earth. The Virgin let her see in a vision the souls which she would save, and Catherine said afterwards that she saw them so clearly that she was sure she would be able to recognise them when she came to meet them again in this life.

At the time the Black Death plague struck Siena, Catherine was passionately engaged in promoting the next crusade among kings and aristocrats. She was also trying to promote peace among Italian cities marred by wars and enmities hardly sparing herself even if it meant having to rebuke kings and popes. It is therefore very telling of Catherine’s great humility and authentic charity that in spite of being involved in what the world would consider “greater and more important causes”, she didn’t lose sight of the needs of the poor and the sick which, for her meant providing spiritually and materially for them when they were alive and honouring their bodies with dignifying care after their death.

We can only be grateful for the inspiring example of this remarkable woman whose generosity the Lord blessed with, among others, the great gifts of unfailing charity and fortitude. Perhaps with Fra Raymond we can ask ourselves what shall I do to honour my Christian calling to be a witness of Christ who himself did not spare his own life for me.