In a time of fear and longing for touch, Fr Colin Carr reflects on Christ healing the leper (homily for the Sixth Sunday in Ordinary Time (B)).

We all have feelings about cleanliness: we spend a lot of time and money on it, or we despise people who spend a lot of time and money on it; or we despise people who don’t spend enough time and money on it. We don’t like to have spots where they shouldn’t be: teenagers can get quite self-conscious about the way they look when their hormones are going crazy. One thing we can be sure of is that it’s quite difficult to be completely rational about cleanliness and spots and so forth.

The attitude to lepers which we find in the torah – the Jewish law – and in Jesus’ time, and in the Middle aAges, and in many countries to this day, is not entirely to do with hygiene. There is something in human societies which seems to need a scapegoat, a group of people onto whom we can pour our fears and loathings and the judgments we don’t want to make about ourselves. If we can push our self-doubt onto others, and blame them for everything that goes wrong, everything that is wrong, it keeps us safe inside our social group. So we exclude lepers; people of a different coloured skin; homosexuals; Jews; asylum-seekers; mentally ill people; people who have AIDS; and so on. We may need isolation wards, quarantine periods and so forth, but the meaning of the word “leper” in most people’s language is not just medical. It’s about isolating an other and coping with our own fear about ourselves.

One of our fears is a fear about our own body. Not many people are completely at ease with the fact that they have – and are – a body. Some religious attitudes teach us to despise the body in favour of the soul; that is not Catholicism, whatever the Penny Catechism used to say. We are saved through our bodies, in and with the body of Christ. I have a feeling that the more we are at ease with our bodies, the less worried we will be by the dirt and diseases in other people’s bodies. We won’t need to exclude them from our clinical human society. I think Hitler was very uncomfortable with his body.

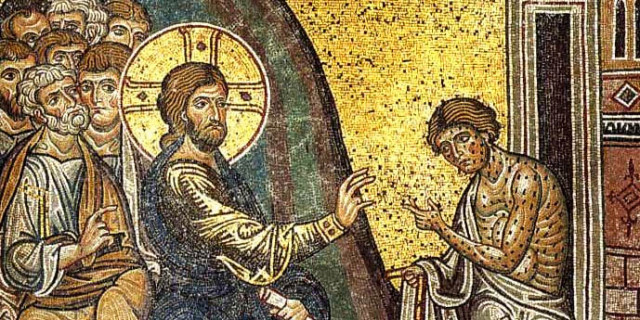

Jesus met a leper who asked to be healed. And Jesus did something very unusual: he touched him; I remember someone coming to the Priory once and telling me he had AIDS. He was after the bus fare to Hexham or something like that. We had a conversation, and when he left I shook his hand, and he thanked me for it – for shaking his hand. I couldn’t figure out why at first, but it dawned on me that he must have met many people who, knowing he had AIDS, wouldn’t shake his hand. For them he was a leper.

Jesus reached across the barriers raised by our fear of others and of ourselves. He was comfortable with himself, with his identity. He was not afraid to touch the untouchable. And he healed him. It was a perfectly good Jewish thing to do, to bring healing. And he insisted that the man should do what Jews do, which is to go and show yourself to the priest, the medicine man. This was to be evidence of his recovery – evidence against people who would say that Jesus was not keeping the Jewish law.

And the man was supposed to keep quiet about what had happened, but naturally he did not. Would you, if you’d been miraculously healed? In fact he became a kind of early evangelist, telling people about Jesus. That would have been alright if people hadn’t wanted to meet this Jesus for themselves; but they did, and he couldn’t move around in the towns for the crowds, so he had to skulk around outside the towns to avoid getting crushed.

So what had happened? He had not only healed the leper: he had by that fact taken upon himself the role of a leper, someone who is not allowed inside the camp, inside the human settlement. He not only healed the leper, he identified with him and took his place as the one who cannot go into the town. Those who would side with the poor will suffer the fate of the poor. This was all just a dress rehearsal for the day when Jesus would be dragged out of the city, the human settlement which had suddenly turned into an inhuman settlement, and was crucified outside the city. There will always be this tendency in human societies to thrust certain people, certain groups, out of the settlement, out of the comfortable home, so that the home can remain comfortable; and Christ, in his followers (not all of them obviously Christian, and many of them despised by those who call themselves Christian) continues to side with the despised and the rejected, and to suffer and to bring the only healing which is available to a world and a Church which are governed by fear.